German soldiers on a Sd.Kfz tractor. 10/4 during the battles for Voronezh

On the morning of June 28, 1942, after artillery and aviation preparation, formations of the Weichs army group went on the offensive against the troops of the left wing of the Bryansk Front.

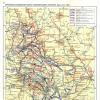

In accordance with the general plan of the fascist German command, the goal of the main operation, which was planned to be carried out in the southwestern strategic direction in the summer of 1942, was to encircle and destroy the troops of the Bryansk, Southwestern and Southern fronts, capture the Stalingrad region and enter the Caucasus. On June 28, the troops of the Weichs group struck in the Voronezh direction and, having broken through the defenses at the junction of the 13th and 40th armies of the Bryansk Front, advanced to a depth of 8–12 kilometers on the very first day.

The balance of forces in the Bryansk, Southwestern and Southern fronts is characterized by the following indicators. Soviet troops numbered 655 thousand people, 744 tanks, 14,196 guns and mortars, 1012 aircraft. The German troops, their allies, had a strength of 900 thousand people, 1263 tanks, 17,035 guns and mortars, 1640 combat aircraft. Thus, the overall ratio was in favor of the enemy, despite the fact that the enemy was superior to our troops in maneuverability.

To organize the first major counterattack of the new tank formations, the Headquarters sent its representative, A.M. Vasilevsky. As usually happens when organizing counterattacks by formations hastily transferred to the breakthrough area, the corps entered the battle one by one. The 4th Tank Corps entered the battle on June 30, and the 17th and 24th Tank Corps only on July 2. The presence of the elite German Richthofen aviation in the air and, as indicated above, the one and a half times superiority of the Germans in the number of personnel and military equipment of all types also did not create objective prerequisites for a successful counter-offensive. It should also be noted that N.V. Feklenko’s weak 17th Corps in artillery was forced to attack the elite “Greater Germany,” whose StuG III self-propelled guns could shoot Soviet tanks with impunity from their long 75-mm guns. Assessing the events near Voronezh at the beginning of the summer campaign of 1942, one must remember that it was here that the full-scale debut of new German armored vehicles took place.

Soviet soldiers surrender to the crew of a German self-propelled gun

The command of the Bryansk and Southwestern Fronts was unable to correctly assess the current situation, did not take into account the instructions of the Headquarters to strengthen the defense in the Voronezh direction, and did not take more decisive measures to establish control and to concentrate forces and assets in dangerous directions in order to create a more favorable ratio for themselves forces in areas of enemy strikes. The defense of the 40th Army, which became the site of the enemy's main attack, was the least prepared in terms of engineering, and the operational density of troops was only one division per 17 km of front. The troops of the 21st and 28th armies, which had suffered heavy losses in previous battles, were not reinforced, and the defensive lines they hastily occupied were poorly prepared. The command of the Southwestern and Southern Fronts also failed to organize a systematic withdrawal of troops along the lines and ensure a strong defense of the Rostov fortified area. The withdrawal took place in extremely difficult conditions. Army commanders and their headquarters lost contact with the troops entrusted to them for several days. As a result of overestimating the reliability of wire communications and underestimating radio communications, firm and continuous command and control of troops was not ensured. Soviet troops suffered heavy losses during defensive battles.

Victory Square in Voronezh

If you have photographs about Operation Blau, please post them in the comments of this post.

Source of photo information.

January 1942 turned out to be extremely difficult for the German armies along the entire Eastern Front. The Wehrmacht retreated all winter - a rapid retreat near Moscow, the failure of the connection with the Finns in the North with the subsequent capture of Leningrad, a difficult encirclement near Demyansk, the evacuation of Rostov-on-Don. Manstein's 11th Army in Crimea failed to take Sevastopol. Moreover, in December 1941, the Red Army troops drove the Germans out of the Kerch Peninsula with an unexpected blow. Hitler had a fit of rage, after which he gave the order to execute the corps commander, Count von Sponeck. In this situation, a new major offensive of the Red Army began - the attack on Kharkov.

The main blow was to be taken by the 6th Army under the command of the new commander Paulus. First of all, he moved the headquarters to Kharkov - where the Russians were rushing. According to the plan adopted by Tymoshenko’s headquarters, Russian units were going to break into the Donbass and create a huge “cauldron” in the Kharkov region. But the Red Army was able to break through the defenses only in the south. The offensive developed successfully, Soviet troops penetrated deeper into the location of German troops, but after two months of fierce fighting, having exhausted all human and material resources, Timoshenko gave the order to go on the defensive.

The 6th Army held out, but Paulus himself had a hard time. Field Marshal von Bock did not hide his dissatisfaction with the slow response of the new commander. Chief of Staff Ferdinand Heim lost his place and Arthur Schmidt was appointed in his place.

On March 28, General Halder went to Rosterburg to present Hitler with plans for the conquest of the Caucasus and southern Russia up to the Volga. At this time, at the Headquarters of the Supreme High Command, Tymoshenko’s project on resuming the offensive on Kharkov was studied.

On April 5, the Fuhrer's headquarters issued orders for the upcoming summer campaign, which was supposed to ensure final victory in the East. Army Group North, during Operation Northern Lights, was called upon to successfully complete the siege of Leningrad and link up with the Finns. And the main blow during Operation Siegfried (later renamed Operation Blau) was supposed to strike in the south of Russia.

Already on the tenth of May, Paulus presented von Bock with an operation plan codenamed “Friedrich,” which provided for the liquidation of the Barvensky ledge that arose during the January offensive of the Red Army. The fears of some German generals were confirmed - having concentrated 640,000 people, 1,200 tanks and about 1,000 aircraft, Tymoshenko on May 12, 6 days before the start of Operation Friedrich, launched an offensive bypassing Volchansk and from the Barvensky salient area with the goal of encircling Kharkov. At first, the matter seemed harmless, but by the evening, Soviet tanks broke through the defenses of Gates' VIII Corps, and individual tank formations of the Red Army were only 15-20 kilometers from Kharkov.

Hurricane fire fell on the positions of the 6th Army. The Wehrmacht suffered huge losses. 16 battalions were destroyed, but Paulus continued to hesitate. At Bock's urging, Halder convinced Hitler that Kleist's 1st Panzer Army could launch a counterattack against the advancing troops from the south. The Luftwaffe was ordered to do everything to slow down the advance by Soviet tanks.

At dawn on May 17, Kleist's 1st Panzer Army attacked from the south. By noon, the tank divisions had advanced 10-15 kilometers. Already in the evening, Timoshenko asked Headquarters for reinforcements. Reserves were allocated, but they could only arrive for several days. Until this time, the General Staff proposed striking at the advancing tank army with the forces of two tank corps and one rifle division. Only on May 19, Timoshenko received permission from Headquarters to go on the defensive, but it was too late. At this time, Paulus's 6th Army went on the offensive in a young direction. As a result, about a quarter of a million soldiers and officers of the Red Army were surrounded. The battles were particularly brutal. For almost a week, the Red Army soldiers fought desperately, trying to break through to their own. Only one Red Army soldier out of ten managed to escape. The 6th and 57th armies that fell into the Barven Mousetrap suffered huge losses. Tens of thousands of soldiers, 2,000 guns and many tanks were captured. German losses amounted to 20,000 people.

On June 1, a meeting was held in Poltava, at which Hitler was present. The Fuhrer hardly mentioned Stalingrad; then for him it was just a city on the map. Hitler highlighted the seizure of the oil fields of the Caucasus as a special task. “If we do not capture Maikop and Grozny,” he said, “I will have to stop the war.” Operation Blau was supposed to begin with the capture of Voronezh. Then it was planned to encircle Soviet troops west of the Don, after which the 6th Army, developing an attack on Stalingrad, ensured the security of the northeastern flank. It was assumed that the Caucasus would be occupied by Kleist's 1st Tank Army and the 17th Army. The 11th Army, after capturing Sevastopol, was supposed to go north.

On June 10, at two o'clock in the morning, several companies of the 297th Infantry Division of Lieutenant General Pfeffer crossed by boat to the right bank of the Donets and, having captured a bridgehead, immediately began to build a 20-meter-long pontoon bridge. By the evening of the next day, the first tanks of Major General Latmann's 14th Panzer Division crossed it. The next day, a bridge further north along the river was captured.

Meanwhile, an event occurred that could undermine the success of the operation. On June 19, Major Reichel, an operations officer of the 23rd Panzer Division, flew to the unit in a light plane. In violation of all the rules, he took with him plans for the upcoming offensive. The plane was shot down, and the documents fell into the hands of Soviet soldiers. Hitler was furious. Ironically, Stalin, who was informed about the documents, did not believe them. He insisted that the Germans would deliver the main blow to Moscow. Having learned that the commander of the Bryansk Front, General Golikov, in whose sector the main actions were to unfold, considered the documents to be authentic, Stalin ordered him to draw up a plan for a preventive offensive in order to liberate Orel.

On June 28, 1942, the 2nd Army and 4th Tank Army launched an offensive in the Voronezh direction, and not at all in the Oryol-Moscow direction, as Stalin assumed. Luftwaffe aircraft dominated the air, and Hoth's tank divisions entered the operational space. Now Stalin gave permission to send several tank brigades to Golikov. Focke-Wulf 189 from the short-range reconnaissance squadron discovered a concentration of equipment, and on July 4, Richthofen’s 8th Air Corps dealt a powerful blow to them.

On June 30, the 6th Army also went on the offensive. The 2nd Hungarian Army was moving on the left flank, and the right flank was covered by the 1st Tank Army. By mid-July, all the fears of the staff officers had dissipated - the 4th Tank Army broke through the defenses of the Soviet troops. But their advance was not calm. The Headquarters of the Supreme High Command came to the conclusion that Voronezh should be defended to the end.

The Battle of Voronezh was a baptism of fire for the 24th Tank Division, which a year ago was the only cavalry division. With the Grossdeutschland SS Division and the 16th Motorized Division on its flanks, the 24th Panzer Division advanced directly towards Voronezh. Its “panzergrenadiers” reached the Don on July 3 and captured a bridgehead on the opposite bank.

On July 3, Hitler again arrived in Poltava for consultations with Field Marshal von Bock. At the end of the meeting, Hitler made a fatal decision - he ordered Bock to continue the attack on Voronezh, leaving one tank corps there, and sending all other tank formations south to Goth.

By this time, Tymoshenko began to conduct a more flexible defense, avoiding encirclement. From Voronezh, the Red Army began to pay more attention to the defense of cities. On July 12, the Stalingrad Front was specially organized by a directive from Headquarters. The 10th NKVD Rifle Division was quickly transferred from the Urals and Siberia. All NKVD flying units, police battalions, two training tank battalions and railway troops came under its control.

In July, Hitler again became impatient with the delays. The tanks stopped because there was not enough fuel. The Fuhrer became even more convinced of the need to quickly capture the Caucasus. This moved him to a fatal step. The main idea of Operation Blau was the offensive of the 6th and 4th Panzer Armies to Stalingrad, and then the offensive to Rostov-on-Don with a general offensive to the Caucasus. Contrary to Halder's advice, Hitler redirected the 4th Panzer Army to the south and took the 40th Panzer Corps from the 6th Army, which immediately slowed down the advance on Stalingrad. Moreover, the Fuhrer divided Army Group South into Group A - the attack on the Caucasus, and Group B - the attack on Stalingrad. Bock was dismissed, blamed for the failure at Voronezh.

Already on July 18, the 40th Tank Corps reached the lower reaches of the Don, capturing the city of Morozovsk, an important railway junction. During the three days of the offensive, the Wehrmacht covered at least two hundred kilometers. On July 19, Stalin ordered the Stalingrad Defense Committee to prepare the city for defense. Headquarters feared that Rostov-on-Don would not hold out for long. The troops of the 17th German Army targeted the city from the south, the 1st Tank Army was advancing from the north, and units of the 4th Tank Army were preparing to cross the Don in order to bypass the city from the east. July 23, when the 13th and 22nd I tank divisions, with the support of the grenadiers of the SS Viking division, reached the bridges over the Don, and fierce battles began for Rostov-on-Don. Soviet soldiers fought with great courage, and NKVD units fought especially stubbornly. By the end of the next day, the Germans had practically captured the city and began a “cleansing” operation.

On July 16, Hitler arrived at his new headquarters, located in Vinnitsa, a small Ukrainian town. The headquarters was called “Werewolf”. The headquarters consisted of several large and very comfortable log buildings erected to the north of the city. To supply food supplies, the German company Zeidenspiner planted a huge vegetable garden near the city.

The Fuhrer's stay in Vinnitsa in the second half of July coincided with a period of extreme heat. The temperature reached plus 40. Hitler did not tolerate the heat well, and the impatience with which he waited for the capture of Rostov only worsened his mood. In the end, he convinced himself so much that the Red Army was on the verge of final defeat that on July 23 he issued Directive No. 45, which effectively canceled out the entire Operation Blau. Hitler ignored strategic rationalism, and now set new, more ambitious tasks for his officers. So, the 6th Army was supposed to capture Stalingrad, and after its capture, send all motorized units to the south and develop an offensive along the Volga to Astrakhan and further, all the way to the Caspian Sea. Army Group A, under the command of Field Marshal List, was to occupy the eastern coast of the Black Sea and capture the Caucasus. Having received this order, List assumed that Hitler had some kind of supernova intelligence. At the same time, Manstein's 11th Army was sent to the Leningrad area, and the SS tank divisions Leibstandarte and Grossdeutschland were sent to France. In place of the departing units, the command placed the armies of the allies - Hungarians, Italians and Romanians.

German tank and motorized divisions continued to move towards the Volga, and Stalingrad was already waiting for them.

Vladimir Beshanov. Hitler's missed chance: Operation Blau

“In the summer of 1942, victory might have been a desirable, but very distant prospect. Not only Great Britain, but also its American, Russian and Chinese allies were forced to limit their plans to the immediate task - to avoid defeat from enemies, whose strength, as it seemed then, was growing and was like an avalanche that had received an impetus ... "

M. Howard "Grand Strategy"

On March 28, 1942, at the Headquarters of Adolf Hitler, Fuhrer of the German nation, Supreme Commander of the Wehrmacht, Commander-in-Chief of the Ground Forces, “the greatest commander of all time,” and so on, a meeting was held at which a plan for the summer campaign was adopted. The outcome of the war, contrary to the iron will of the “battery of the German people,” was still being decided in the East. Therefore, the main tasks assigned to the Wehrmacht were to seize the initiative from the Red Army, which had not been defeated due to a misunderstanding, which had basely used the elemental forces of nature in its favor - dirt, frost, roads, commissars - to finally destroy its manpower and deprive the Soviet Union of its most important economic centers.

Since there were no longer enough forces and means for an offensive in all strategic directions laid down in the ingloriously deceased Barbarossa plan, the Fuhrer, guided primarily by economic considerations, decided to concentrate efforts on the southern wing of the Eastern Front. Here, during the “main operation,” it was planned to completely capture the industrial Donetsk basin, the wheat fields of the Kuban, the oil-bearing regions of the Caucasus and the passes through the Caucasus ridge. In the north, “as soon as the situation allowed,” it was necessary to capture Leningrad and establish contact with the Finns; in the central sector of the front, it was necessary to conduct restraining actions with minimal forces. Moscow, as a target for the offensive, was no longer needed.

It was believed that if successful, no Anglo-American assistance would compensate I.V. Stalin lost resources. In the future, Hitler intended to create an “Eastern Wall” against the Russians - a gigantic defensive line - in order to then strike England through the Middle East and North Africa. In the captured part of Russia, it was necessary to begin a 30-year program of colonization of the “living space,” encouraging in every possible way the Aryans’ desire to move to the East, “the desire to increase the birth rate,” a sense of their racial exclusivity and historical role, a clear understanding of the primitiveness of the “non-Nordic biological mass,” doomed to partial destruction, Germanization, and deportation to Siberia.

The appearance of American troops in the European theater of operations was expected no earlier than a year later, since everyone understood: “The United States was in the initial stages of mobilizing its enormous resources and was dealing with issues of an administrative, economic and political nature that were completely unfamiliar to the people of the United States.”

On April 5, 1942, the Fuhrer signed OKW Directive No. 41. According to this document, the main set of operations for the upcoming campaign consisted of a series of successive interconnected and complementary deep strikes, each time ensuring “maximum concentration in decisive areas.” The goal of the first operation, which received the code name “Blau” on April 7, was a breakthrough from the Orel region to Voronezh, from where tank and motorized divisions were to turn south and, in cooperation with troops advancing from Kharkov, destroy the Red Army forces between the Don and Seversky rivers Donets. This was to be followed by an attack by two army groups on Stalingrad, capturing the enemy in a pincer movement from the northwest (downstream of the Don) and from the southwest (upstream of the Don). In parallel with the advance of mobile troops to cover their left flank from the Orel area to Voronezh and further along the banks of the Don, powerful positions, rich in anti-tank weapons, had to be equipped, which were intended to be held by formations of Germany’s allies. And, finally, a turn to the Caucasus - to the coveted oil and the “Indies” looming on the horizon. The ultimate goal of the “main operation” of 1942 was to conquer the Caucasian oil fields.

Operation Blau was due to begin in June. Before this, in order to create favorable conditions, it was planned to carry out offensive operations with a limited purpose - in the Crimea and in the Izyum direction.

The result was a risky multi-step combination that required constant maneuvering of forces, organization of their continuous interaction and uninterrupted supply at a great distance from the “domestic base.” Only the Wehrmacht was able to implement such a complex plan at that time, and even it “didn’t work out.” Although, according to the British military theorist B. Liddell-Hart, “it was a subtle calculation that was closer to its goal than is generally believed after its final and catastrophic failure.”

Let us add that for the Third Reich this was the last chance to win, or at least not lose, the Second World War.

At Soviet Headquarters, after the defeat of the Germans near Moscow, the party and military generals were filled with the most decisive intentions. In May Day Order No. 130, Comrade Stalin, “a brilliant leader and teacher of the party, a great strategist of the socialist revolution, a wise leader of the Soviet state and commander,” set a specific task for the Red Army: “To ensure that 1942 becomes the year of the final defeat of the Nazi troops and the liberation of Soviet land from Hitler’s scoundrels.” The idea for the spring-summer campaign was to consistently carry out a series of strategic operations in different directions, forcing the enemy to disperse his reserves, not allowing him to create a strong group at any point, beat him with “mighty blows” and drive him to the West without stopping. . The defeat of the Wehrmacht was supposed to begin with the attacks of the Southwestern Front on Kharkov - Dnepropetrovsk scheduled for May and the expulsion of the Germans from the Crimean Peninsula. After this, the troops of the Bryansk Front went on the offensive in the Lgov-Kursk direction. Then it was the turn of the Western and Kalinin fronts to eliminate the enemy’s Rzhev-Vyazma grouping. In conclusion, the liberation of Leningrad and the entry of the Karelian Front to the state border line of the USSR: “The initiative is now in our hands, and the efforts of Hitler’s loose rusty machine cannot hold back the pressure of the Red Army. The day is not far when red banners will again fly victoriously throughout Soviet land.”

Headquarters correctly calculated that the Wehrmacht was no longer capable of conducting large-scale offensive operations in all directions, but mistakenly believed that Moscow remained Hitler’s main goal. Even after the war, having in hand the documents of the German General Staff, Soviet historians did not dare to doubt the forecasts of Comrade Stalin himself: “Contrary to the lessons of the winter campaign, the German command, just as in 1941, set the capture of Moscow as its central and decisive task. to force the Red Army to capitulate and thus achieve the end of the war in the East.” Therefore, most of the forces of the active army were concentrated in the Moscow direction, and 10 reserve armies were evenly distributed along the entire Soviet-German front.

The successes of the military industry made it possible to begin the formation of tank corps, and in May the creation of such powerful operational formations as tank and air armies began. However, it was May that marked the beginning of a series of catastrophic defeats. The Rzhev-Vyazma operation of the Kalinin and Western fronts turned out to be a major failure (only numbers remained from the 29th and 33rd armies), the agony of the 2nd shock army began in the Lyuban “bottle”, the troops of the Crimean Front were defeated by the rapid counter-offensive of General Manstein ( The 44th, 47th, 51st armies lost more than 70% of their personnel and all their equipment). The troops of the Southwestern Front (6th, 57th, 9th armies), advancing on Kharkov, themselves got into the “bag” just when the Germans started to liquidate it. The total human losses of the Red Army in the first half of 1942 amounted to more than 3.2 million commanders and Red Army soldiers, that is, 60% of its average strength, with 1.4 million being irrecoverable losses. Germany's losses in killed and missing in all theaters during the same period reached 245.5 thousand soldiers and officers; The ground forces, according to entries in the diary of the OKH chief of staff, Colonel-General F. Halder, lost 123 thousand people killed and 346 thousand wounded on the Eastern Front - 14.6% of the average number of 3.2 million.

Thus, by mid-June, the German command was able to create favorable conditions for the Wehrmacht’s strategic offensive.

To achieve their goals, Germany and its allies concentrated 94 divisions, including 10 tank and 8 motorized, on the southern wing of the Eastern Front. They consisted of 900 thousand people, 1,260 tanks and assault guns, more than 17,000 guns and mortars, supported by 1,200 combat aircraft of the 4th Air Fleet. Of these, 15 divisions were in Crimea.

An army group under the command of General von Weichs, consisting of the 2nd German Field and 4th Panzer Armies, as well as the 2nd Hungarian Armies, in cooperation with the 6th Army of General Paulus, was aimed at carrying out Operation Blau. Her plan was to launch two strikes in converging directions on Voronezh. As a result, it was planned to encircle and defeat Soviet troops west of the city of Stary Oskol, reach the Don in the section from Voronezh to Staraya Kalitva, after which the 4th Tank and 6th armies were supposed to turn south, towards Kantemirovka - to the rear of the main forces of the South -Western Front Marshal S.K. Timoshenko (21st, 28th, 38th, remnants of the 9th and 57th armies).

The second strike group - the 1st Tank and 17th Field Armies - from the Slavyansk area was to break through the Soviet front and, with a strike on Starobelsk and Millerovo, complete the encirclement of the troops of the Southwestern and Southern Fronts.

In the 6,00-km strip from Orel to Taganrog, Field Marshal von Bock’s Army Group “South” was opposed by the troops of the Bryansk, South-Western and Southern Fronts, which included 74 divisions, 6 fortified areas, 17 rifle and motorized rifle brigades, 20 separate tank brigades, 6 tank corps - 1.3 million people, at least 1,500 tanks. Air cover was provided by 1,500 aircraft from the 2nd, 8th and 4th Air Armies and two ADD divisions.

According to the plan, which, by the way, accidentally fell into the hands of the Soviet command, but was perceived by them as deliberately planted disinformation, the Weichs group, with the support of the 8th Air Corps, launched a surprise attack from the Shchigra area at the junction of the 13th and 40th armies of Bryansk front. In the center, along the Kursk-Voronezh railway, the 4th Tank Army of General Hoth, which included 3 tank (9, 11, 24th) and 3 motorized (3, 16th and “Greater Germany”), was rushing towards the Don. ) divisions. To the south, the 2nd Hungarian Army - 9 infantry and 1 tank divisions - was advancing on Stary Oskol. The northern flank of the strike force was covered by the 55th Army Corps of the 2nd German Army.

On the very first day, the Germans penetrated 15 km into the Soviet defense; on the second, the Panzers destroyed the headquarters of the 40th Army, completely disorganizing its command and control, and entered the operational space. Since June 29, the commander of the Bryansk Front, Lieutenant General F.I. Golikov tried to eliminate the breakthrough with flank attacks from five tank corps (1, 4, 24, 17, 16, 24) and separate tank brigades, but acted in the best traditions of the summer of 1941. The corps entered the battle on the move, piecemeal, uncoordinated in time, without reconnaissance, without interaction with other branches of the military, without communication with each other and higher headquarters. One by one they were defeated.

On June 30, the troops of the 6th Army of General Paulus, which had two tank (3rd, 23rd) and 29th motorized divisions as part of the 40th Tank Corps, went on the offensive from the Volchansk region, with the support of the 4th Air Corps “unexpectedly quickly broke through the Soviet defenses at the junction of the 21st and 28th armies of the Southwestern Front and advanced up to 80 km in three days. On July 3, they met with Hungarian units at Stary Oskol, closing the encirclement ring around six Soviet divisions. After this, the main forces of Weichs rushed to Voronezh, Paulus - to Ostrogozhsk, covering the right flank of the 28th Army of Lieutenant General D.I. Ryabysheva.

On July 5, the 6th Army crossed the Tikhaya Sosna River with its left wing, and the Great Germany Division and the 24th Tank Division broke into Voronezh. On the evening of the same day, a categorical order came from the Fuhrer's Headquarters to suspend the assault on the city, withdraw mobile units from street battles and send them south, to the corridor between the Don and the Seversky Donets.

While Hitler stated at the meeting that the capture of Voronezh did not matter to him, Stalin, fearing that the Germans would start a detour movement from here to the rear of Moscow, paid special attention to this direction. From the Stavka reserve, the 3rd and 6th reserve armies advanced to the Don, renamed the 60th and 6th respectively (13 fresh rifle divisions). At the same time, a powerful counterattack was being prepared by the forces of the 5th Tank Army (2, 11, 7th Tank Corps, 19th Separate Tank Brigade, 340th Rifle Division). The 1st Fighter Aviation Army of the Headquarters reserve (230 aircraft) was redeployed to the Yelets area. To “provide assistance in organizing the defense of Voronezh,” the Chief of the General Staff A.M. rushed from Moscow. Vasilevsky, his deputy N.V. Vatutin, head of the Main Armored Directorate Ya.N. Fedorenko.

On the morning of July 6, the 5th Tank Army attempted to intercept Hoth's communications with a strike from the north and disrupt the enemy's crossing of the Don. By this time, the 4th Tank Army was already turning south, and in its place, the infantry of the 2nd Field Army was digging in with a front to the north. As before, Soviet corps were introduced into battle one by one, on the move, without preparation, on a wide front. The German infantry, with the assistance of the 9th and 11th Panzer Divisions, successfully repulsed the disorganized Russian attacks. At this point, the 5th Panzer Army, which had delayed Hoth's formations for four days, ceased to exist and was disbanded.

The gap between the Bryansk and Southwestern fronts reached 300 km wide and up to 170 km deep. On July 7, the Voronezh Front was formed, which included the 60th, 40th, 6th combined arms, 2nd air armies, 4th, 17th, 18th, 24th tank corps, which received the task of “firmly gaining a foothold” and in whatever began to hold the eastern bank of the Don. On the opposite bank, the Hungarians took up defensive positions with similar intentions.

The immediate task of the offensive was completed. Over the nine days of the battle, Soviet losses amounted to 162 thousand people. According to German data, 73 thousand Red Army soldiers were captured and 1200 tanks were destroyed.

Army Group South split into two parts on July 7. Field Marshal von Bock took over Group B, which included the 4th Panzer, 2nd and 6th Field, 2nd Hungarian and 8th Italian Armies. They had to continue the offensive, while simultaneously organizing defense at the turn of the Don River. The newly created command of Group A took over the 17th Field and 1st Tank Armies. Field Marshal List was entrusted with the leadership of the operations to attack Stalingrad from the southwest.

The first half of July 1942 passed to the sounds of fanfare in honor of the victories of German weapons.

In North Africa, German-Italian forces defeated the British 8th Army and captured Tobruk. General Rommel's tank corps, having traveled 600 km through the desert, reached El Alamein, a railway station located 100 km from Alexandria. The battle for Egypt reached its climax. The English fleet was forced to leave for the Red Sea. The British headquarters had already worked out plans for the retreat of the 8th British Army to Palestine if it failed to hold the Nile Delta.

On July 1, Sevastopol fell, and the entire Crimean Peninsula was in German hands - a base for the fleet, an airfield for aviation and a springboard for the jump to the Caucasus. Accordingly, Manstein's 11th Army was released to participate in hostilities in the south, and for this occasion he was awarded the rank of field marshal. After rest and replenishment, the army was supposed to be transferred through the Kerch Strait to the Taman Peninsula (Operation Blucher).

In the Atlantic, Grand Admiral Dennitz’s “wolf packs” sank 700–800 thousand tons of allied ships every month.

In the North, German submarines and aircraft destroyed convoy PQ-17. Of the 34 transports traveling from Iceland to the port of Arkhangelsk, 23 were sunk. At the bottom of the Barents Sea were 3,350 vehicles, 430 tanks, 210 aircraft and about 100 thousand tons of cargo. The destruction of the convoy in Berlin was regarded as a major victory, equivalent to the defeat of an army of 100,000. The consequences were even more severe: at the request of the British Admiralty, supplies of military materials to the USSR along the Northern Route, associated with “unjustified risk,” were suspended for almost six months. Attempts to organize supplies for the Soviet Union through the Persian Gulf were thwarted due to the low capacity of the southern ports, the lack of anything resembling a road network in the Middle East, the lack of vehicles, and the need to meet the needs of British troops stationed in Iran and Iraq. 15 thousand tons of cargo per month is all that fell to the Russians in the summer of 1942.

Meanwhile, the second stage of the Wehrmacht's summer offensive was unfolding on the southern wing of the Eastern Front.

On the evening of July 7, the 40th Tank and 8th Army Corps of Paulus' Army, developing an offensive along the right bank of the Don, occupied Rossosh, cut the Moscow-Rostov railway, and the next day captured bridgeheads on the southern bank of the Chernaya Kalitva River. The “weakly controlled units” of the 21st and 28th armies of the Southwestern Front rolled back here, across the river. On July 8, General von Kleist's 1st Panzer Army launched an attack from the Slavyansk region through the Seversky Donets in the general direction of Millerovo, and General Ruoff's 17th Panzer Army from Artyomovsk attacked Voroshilovgrad.

Tymoshenko's headquarters did not understand the situation and increasingly lost control of the troops. July 9, commander of Army 38, Major General K.S. Moskalenko, having no connection with the higher command, made an independent decision to turn the right flank of the army to the north in order to organize defense in the Kantemirovka area, but von Schweppenburg's 40th Panzer Corps was already bypassing Kantemirovka from the east. By the end of July 11, the main forces of the Southwestern Front, covered from the northeast and east and attacked from the west by Kleist’s tank army, found themselves forced to fight heavy battles south and southwest of Kantemirovka. The advanced units of the 40th Tank Corps reached the village of Bokovskaya on the Chir River. A day later, the 1st Tank Army, with Mackensen's group (16th, 22nd, 14th tank, 60th motorized divisions) in the vanguard, crossed the Aidar River south of Starobelsk on a broad front and rushed to Millerovo, where a meeting with units of 4 was scheduled 1st Tank Army, 17th Army with its left flank approached Voroshilovgrad.

The Southwestern Front, which had a strength of 610 thousand people before the start of Operation Blau, lost 233 thousand, was divided into separate groups of troops and actually collapsed. On July 12, the Headquarters decided to abolish it. Units of the 28th, 38th, and 9th armies were transferred to the Southern Front under Lieutenant General R.Ya. Malinovsky (37th, 12th, 18th, 56th, 24th armies), who was tasked with stopping the enemy’s advance. True, there was nothing to transfer, and it didn’t work out - the shattered armies, under the pressure of circumstances, moved along their own trajectories, and Marshal Timoshenko could not answer Moscow’s question: “Where did these divisions go?” The bloodless formations of the 28th and 38th armies “in an unorganized and uncontrollable mass” broke through to the northeast, the 9th Army rolled back to the south. At the same time, the formation of the Stalingrad Front began, which was to include the 63rd, 62nd, 64th (former 5th, 7th, 1st reserve - 19 divisions, more than 200 thousand people), 21st armies, as well as the 28th, 38th and 57th, from which only headquarters remained. The new front received the task: to firmly defend the line along the Don River from Pavlovskaya to Kletskaya, then along the line of Kletskaya, Surovikino, Suvorovsky, Verkhnekurmoyarskaya and prevent the enemy from reaching the Volga.

Commander of the Southern Front, Lieutenant General R.Ya. Malinovsky initially decided to stop the German troops at the line Millerovo, Petropavlovsk, Cherkasskoye, but it was too late... too late... The enemy was ahead of the pace. General Halder wrote with satisfaction on July 12: “In the zone of operations in the south, a picture is emerging that is quite consistent with the plans.”

However, the very next day Hitler began to improvise and break the already fragile plan. Having decided that Tymoshenko’s main forces, fleeing the German “pincers,” were retreating to the south, the Fuhrer planned to build a grandiose “cauldron” north of Rostov. To this end, on July 13, he ordered both tank armies to move in an accelerated march to the mouth of the Seversky Donets River and turn west along the Don to cut off the Russians from crossings, and then destroy the enemy together with the 17th Army. At the same time, the 1st Tank Army had to cross the Donets once again. The 4th Tank Army was reassigned to Army Group A. Thus, the offensive of the tank and motorized divisions on Stalingrad was postponed; only the 6th Field Army continued to advance to the east, from which, moreover, the 40th Tank Corps was taken away in favor of Hoth. At the same time, Field Marshal Bock was removed from his post, and General Weichs was appointed in his place.

On July 15, German tank corps met east of Millerovo. Formations of the 24th Army of Lieutenant General I.K. Smirnov, advanced from the reserve of the Southern Front, tried to open the outer ring of encirclement, but were defeated and thrown back to Kamensk by attacks from moving units. On this day, the Headquarters ordered the immediate withdrawal of the troops of the Southern Front beyond the Don and, in cooperation with the 51st Army of the North Caucasus Front, to organize a strong defense along the southern bank of the river in the area from Bataysk to Verkhnekurmoyarskaya. The defense of the Rostov fortified area from the north was entrusted to the 56th Army of Major General A.I. Ryzhova. On July 17, Ruoff's troops took Voroshilovgrad, Kleist's tankers crossed the Seversky Donets in the opposite direction and took a bridgehead in the Kamensk-Shakhtinsky area. Hoth's motorized divisions reached the Don east of the mouth of the Donets. They had to cross the river and then, turning west, go along the southern bank to the rear of the Rostov position. At this time, in the forest near Vinnitsa, where the General Staff had moved with Hitler, Halder, doubting the presence of large Russian forces in the prepared trap, strongly objected to the “senseless concentration of forces around Rostov” and suggested, without wasting expensive summer time and precious fuel, empty maneuvers, finally move on to the Stalingrad operation. A little later, the general will write: “Even to an amateur it becomes clear that all mobile forces are concentrated near Rostov, no one knows why...”

On July 20, Kleist's 1st Panzer Army launched an attack from Kamensk to Novocherkassk. A day later, General Kirchner’s 57th Tank Corps moved from the area north of Taganrog to attack Rostov. Hoth's army captured bridgeheads on the southern bank of the Don in the areas of Konstantinovskaya and Tsimlyanskaya. The attack on the Rostov fortified area began on July 22; On the 23rd, divisions of the 3rd Tank Corps broke into the city. But the demonstration “cauldron” did not work out - Malinovsky’s armies, sometimes in a planned manner, sometimes at a run, went beyond the Don.

The troops of three Soviet fronts avoided encirclements similar to those in Kyiv or Kharkov, but since June 28, they lost 568 thousand people (of which 370 thousand were irrevocable), 2,436 tanks, 13,716 guns and mortars, 783 combat aircraft, and almost half a million small arms. The irretrievable losses of the Wehrmacht during a month of fighting in all theaters of war amounted to 37 thousand soldiers and officers (on the entire Eastern Front - 22 thousand), 393 tanks and assault guns.

The strategic line of the Red Army in the south was broken through to a depth of 150–400 km, which allowed the enemy to launch an offensive in the large bend of the Don towards Stalingrad. However, at that moment, like a bolt from the blue, Directive No. 45 “On the continuation of Operation Brunswick” struck.

Hitler convinced himself that the Russians were now definitely at the limit of their strength, and considered it possible to change the plan of the campaign.

The fundamental point of Operation Blau (from June 30 - “Brunschweig”) was the rapid advance of Army Groups “B” and “A” towards Stalingrad and the encirclement of the retreating Soviet troops. Following this, an attack on the Caucasus was to begin. However, Hitler was in such a hurry to seize Grozny and Baku oil that he decided to carry out these operations simultaneously. Contrary to Halder's objections, the Fuhrer redirected both tank armies to the south and took the 40th Panzer Corps from Paulus. Of the mobile formations in the 6th Army, only one motorized division remained.

Hitler feared that by throwing his main forces at Stalingrad, he would strike at an empty place and waste time. In a directive signed on July 23, he approved a “fatal decision”: instead of the initially envisaged echelon operations, he ordered two simultaneous offensives in divergent directions - to the Volga and to the Caucasus.

The troops received new tasks, new deadlines and no reinforcements. Moreover, considering that the available forces are quite sufficient for the final defeat of the Russians on the southern wing, the Fuhrer transferred two motorized ("Adolf Hitler" and "Great Germany") and two infantry divisions from Army Group "A" to France and Army Group " Center", two tank divisions (9th and 11th) - to Army Group Center. Manstein's army set out to storm Leningrad. In total, by the end of July, 11 German divisions were withdrawn from the main direction. Finally, the command of the reserve army had to equip and send three new infantry divisions to the West as quickly as possible - to the detriment of the replenishment of the Eastern Front.

If on June 28, as part of Army Group South, 68 German divisions and 26 allied divisions were concentrated on an 800 km front, then by August 1 there were 57 German and 36 allied divisions to carry out new tasks. The front line at this time was already about 1200 km. Nominally, the total number of formations remained unchanged, but the Germans themselves quite reasonably considered the combat power of the Italian, Romanian or Hungarian division to be equal to half of the German one. These forces now had to capture and hold a strip of 4,100 km. Not to mention the transportation and supply difficulties that were bound to arise, the strategic goal no longer corresponded in any way to the available means.

“July 23,” writes General Doerr, “apparently can be considered the day when the High Command of the German Army clearly showed that it did not follow the classical laws of warfare and embarked on a new path, which was largely dictated by the willfulness and illogicality of Hitler than the rational, realistic way of thinking of a soldier."

General Halder openly opposed yet another “brilliant insight.” The relationship between the Supreme Commander-in-Chief and the Chief of the OKH General Staff became tense to the limit. Like any dictator, Hitler did not trust generals who had the habit of thinking independently and “not trained in unconditional obedience,” especially in such an important matter as waging war. Specifically, Halder, who constantly intervened in the grand strategy with his warnings and academic judgments, he called behind his back a stupid person, and his headquarters - “a nest of conspirators and traitors.” Halder steadfastly hated the Fuhrer and more than once mentally tried on a “wooden pea coat” on him. In the end, the general expressed everything he thought about the Fuhrer’s ability to lead military operations, and Hitler, furious, told him to shut up. The court doctor Morel explained the increased irritability of the participants in the dispute due to the harmful continental climate of Vinnitsa.

So, the main efforts were aimed at conquering the Caucasus. But already on July 26, Paulus’s army got stuck in the defense of the Stalingrad Front for the first time. Five days later, Hitler ordered the return of the 4th Panzer Army to Army Group B. From this moment on, two approximately identical German groups advanced at right angles to each other. Subsequently, the Fuhrer transferred troops at his own discretion. Like a Buridan donkey, he could not make a choice between two “armfuls of hay.” Permanent changes to approved plans disrupted the already difficult work of supply services.

The rest is known: German forces, together with the allies, were not enough in any of the directions. Hitler had to throw more and more divisions at Stalingrad, but the Russians did it faster. As a result, Paulus was drawn into an “all-consuming vortex” in which his entire army perished. Kleist got stuck in the Caucasus, and a little later he barely escaped. The Russians won the race against the clock, although everything hung in the balance.

But, frankly speaking, it is not clear how the Battle of Stalingrad could have been blown away. It can be assumed that the Fuhrer was an agent of influence of the Comintern. After all, everything was calculated down to the smallest detail, calculated correctly, this was confirmed by three impeccably conducted stages of the summer campaign. Stalingrad lay literally on a silver platter. It was only necessary to continue winning at pace, or, as Halder formulated back in the planning period, “the Russians must throw their forces after ours.” Everything could have been completely different. Like that.

On July 14, at five o'clock in the afternoon, Hitler finished his favorite chamomile tea with dumplings, leaned back in his chair and very intelligently said: “You know, Franz Maximilianovich, you convinced me. Let's not force things."

On the morning of July 15, the 4th Tank Army (24th, 48th Tank, 4th Army Corps), having returned the 40th Tank Corps to the subordination of General Paulus, from the area northeast of Millerovo began moving east to Stalingrad. Ahead, all the way to the horizon, lay a burnt-out steppe, cut up by ravines and streams - and no sign of the Russians. To the north, in the same direction, without encountering resistance, covered from the left flank by the Don and the barriers of the 29th Army Corps, at an average pace of 30 km per day, the columns of the 6th Field Army were gathering dust. “Today it’s 50 degrees hot,” wrote non-commissioned officer of the artillery regiment of the 297th Infantry Division Alois Heimesser. “There are infantrymen lying fainted along the road; over a kilometer I counted 27 people.” The Schweppenburg Panzer Corps, quietly scolding the staff strategists, again turned 90 degrees. The 1st Tank Army (3rd Tank, 44th, 51st Army Corps) continued to roll south, deeply enveloping Malinovsky's right wing. The left wing, from Taganrog, was hit by the 57th and 14th tank corps.

On the night of July 16, the troops of the Southern Front began to retreat to the line indicated by Headquarters. In the afternoon, Kleist's army occupied Tatsinskaya. Alfred Rimmer, a soldier of the motorized infantry regiment of the 16th Panzer Division, wrote in his diary: “We set out at 6 o’clock. We drove 170 kilometers. The Russian retreat road along which we were traveling clearly shows their unplanned, wild flight. They abandoned everything that was a burden to them in flight: machine guns, mortars and even a “hell gun” with 16 charges of 10 cm caliber, which is charged and fired with electricity.” The 40th Tank Corps (3rd, 23rd Tank, 29th Motorized, 100th Jaeger Divisions) crossed the Chir River at the villages of Bokovskaya and Chernyshevskaya and entered into battle with the advanced detachments of the Russians. A day later, the 48th (24th Panzer, Motorized Division "Gross Germany") and 24th (14th Panzer, 3rd, 16th Motorized Divisions) Corps of the 4th Panzer Army reached the Tsimla River in its upper reaches.

By this time, in the bend of the Don, having made a 100-km march from Stalingrad on foot, only the 62nd Army under the command of Major General V. Ya Kolpakchi managed to deploy. The line of defense for it was chosen unsuccessfully: in open, tank-accessible terrain, without taking into account natural barriers that could be strengthened by engineering barriers and made difficult for the attacking side to reach, “the positions were placed in the bare steppe, open to observation and viewing them both from the ground, and from the air." However, there were no mines or other means of obstruction available, so the fighters simply dug holes in the open field, called single rifle cells. The army, which had a total strength of 81 thousand people, included 6 rifle divisions, 4 cadet regiments of military infantry schools, 6 separate tank battalions (250 tanks), and eight artillery regiments of the RGK. Five divisions of the first echelon stretched out in a thread from north to south from Kletskaya to Nizhne-Solonovsky on a front of almost 130 km, then there was a 50-km gap to Verkhne-Kurmoyarskaya. One rifle division was in the second echelon near the railway to Stalingrad. One rifle regiment with reinforcements was assigned from each rifle division to forward detachments, deployed 60–80 km from the main forces in order to find and “probe” the enemy.

The 64th Army, which was transferred from the Tula region (for some reason without the commander who formed it), barely began unloading at several stations far from the front line. As Deputy Commander V.I. recalls. Chuikov, on July 17, he received a directive from the front headquarters to deploy the army on the front from Surovikino to Verkhnekurmoyarskaya within two days, replacing the left-flank divisions of General Kolpakchi here, and put up a tough defense:

“The task set by the directive was clearly impossible, since the divisions and army units were just unloading from the trains and heading west, to the Don, not in combat columns, but in the same composition as they followed along the railway. The heads of some divisions were already approaching the Don, and their tails were on the banks of the Volga, or even in wagons. The rear units of the army and army reserves were generally in the Tula area and were waiting to be loaded into railway cars.

The army troops had to not only be collected after unloading from the trains, but also transported across the Don, covering 120–150 kilometers on foot...

I went to the head of the operations department of the front headquarters, Colonel Rukhla, and, having proven the impossibility of fulfilling the directive on time, asked him to report to the Front Military Council that the 64th Army could occupy a defensive line no earlier than July 23.

With such a dense formation, the Soviet side had no chance of withstanding a strong enemy strike, especially a strike from mobile formations. The vast majority of reserve army personnel had no combat experience. Nevertheless, “the mood at the headquarters of the 62nd Army was high.” The fact is that the command of the Stalingrad Front, quite optimistically assessing the immediate prospects, considered its direction auxiliary and in a report to the General Staff predicted that the main blow “the enemy will deliver in the lower reaches of the river.” Don with the aim of breaking through to the North Caucasus."

On the morning of July 18, von Schweppenburg's corps from the Perelazovsky area struck the right flank of the 62nd Army. A day later, tanks destroyed the headquarters of the 192nd and 184th rifle divisions in the Verkhne-Buzinovka area and reached the Don near Kamenskaya. German aviation, supporting the actions of ground troops, absolutely dominated the air. On the left flank of the formation of the 4th Tank Army, they scattered the 196th Infantry Division to the wind, reached the mouth of the Chir River and captured a bridgehead on the northern bank. On July 20, the “pincers” closed, a “cauldron” was formed west of Kalach for four Soviet divisions and the 40th tank brigade. Their remnants, abandoning artillery and equipment, leaked out of the encirclement to the east in small groups.

The path to Stalingrad was actually open. However, further advance was hampered by a lack of fuel and a significant lag of the infantry. The Germans spent the next four days clearing the area in the small bend of the Don, accumulating supplies and regrouping forces.

In the zone of Army Group A, Ruoff's army captured Voroshilovgrad on July 17 and developed an offensive towards Rostov. Kleist's infantry corps repelled the relief attack of the 24th Army at the line of the Seversky Donets, and the 3rd Tank Corps (22, 16th Tank, 60th Motorized Divisions) of General Mackensen crossed the Don south of Tsimlyanskaya on July 20. On July 24, Rostov fell, on the 26th, having crossed the river, the 125th and 73rd infantry divisions, after fierce fighting, captured Bataysk; nearby, near Aksayskaya, another bridgehead was created by the 13th tank and 198th infantry divisions.

A new catastrophe was brewing on the southern wing of the Soviet-German front. The Germans had about 70 km to go in a straight line to Stalingrad. There were no serious natural barriers or organized defense along this path. On the 200-km section from Sirotinskaya to Verkhnekurmoyarskaya along the left bank of the Don, the Soviet command had six fairly battered rifle divisions of the 62nd Army, which had lost half of their strength, headed by Lieutenant General A.I. Lopatin, as well as four divisions, two naval infantry and the 137th tank brigade of the 64th Army under Lieutenant General V.I. Chuikova. As a means of rapid response, their defense was “propped up” by the restored 13th Tank Corps (157 tanks) of Colonel T.I. Tanaschishina - fortunately, STZ continued to uninterruptedly supply brand new Thirty-Fours to the front line. The northern arc of the Don bend from the mouth of the Medveditsa River was covered by a curtain of six divisions of the 64th Army of Lieutenant General V.I. Kuznetsov, stretching over 300 km (with the width of the bands for each division from 40 to 100 km), the southern - four rifle and two cavalry divisions of the 51st Army of Major General N.Ya. Kirichenko.

The front reserve included two rifle divisions (18th and 131st), two tank brigades (133rd, 131st) and the 3rd Guards Cavalry Corps. On July 22, a decision was made to form, on the basis of the directorates of the 38th and 28th combined arms armies, two tank armies of mixed composition - the 1st under the command of Major General K.S. Moskalenko and the 4th under the command of Major General V.D. Kryuchenkin, - which were to include the 13th, 28th, 22nd, 23rd tank corps, separate tank brigades and rifle formations. Another 6 tank brigades were being reorganized in the city. Headquarters reserves were hastily transferred to Stalingrad. Troops of the 8th, 2nd, and 9th reserve armies were loaded in Saratov, Vologda, and Gorky. Trains with the 204th, 126th, 205th, 321st, 399th, and 422nd personnel rifle divisions were rushing from the Far East, although their arrival was expected no earlier than July 27–28. In connection with the rapidly deteriorating situation, the city Defense Committee adopted a resolution on preparations for special measures - mining and destruction of industrial enterprises, communications centers, energy facilities, water supply and other facilities.

Defeats and endless retreats demoralized the Soviet troops and undermined their faith in victory and in the ability of military leaders to repel the Germans. Special departments and divisions of military censorship recorded the growth of defeatist sentiments and anti-Soviet statements on the part of soldiers and commanders: “They don’t know how to command, they give several orders, and then they are canceled ...”, “We were betrayed. Five armies were thrown to the Germans to be devoured. Someone is currying favor with Hitler. The front is open and the situation is hopeless,” “The German army is more cultured and stronger than our army. We can’t defeat the Germans,” “Tymoshenko is a bad warrior, and he’s ruining the army.” July 23 Marshal S.K. Timoshenko, who had been plagued by continuous failures since May 1942, was removed from command of the Stalingrad Front. His place was taken at the wrong time and due to his abilities by Lieutenant General V.N. Gordov, famous for his “obscene management”. On the same day, Stalin’s order No. 227 appeared: “We have lost more than 70 million people, more than 800 million pounds of grain per year and more than 10 million tons of steel. We no longer have a superiority over the Germans either in human reserves or in grain reserves. To retreat further means to ruin ourselves and at the same time ruin our Motherland. Every new piece of territory we leave behind will strengthen the enemy in every possible way and weaken our defenses in every possible way...”

Meanwhile, Paulus concentrated the main forces of the 6th Army (40th Tank, 8th, 17th Army Corps) at Vertyachiy to cross the Don in the easternmost part of the bend. On the right, at Kalach, the 71st Infantry Division was supposed to deliver an auxiliary attack. The main forces of the 4th Tank Army (48th, 24th Tank, 4th Army Corps) prepared for an attack in the Verkhnechirskaya area, south of the railway to Stalingrad, at the junction of the 64th and 62nd armies. The action plan of Army Group B was simple: both armies - the 4th Panzer to the south, and the 6th Army to the north of Stalingrad - struck in the direction of the Volga, turned left and right at the river, respectively, and took the entire Stalingrad area in pincers with the troops defending it.

But the first, on July 24, from the bridgehead at Tsimlyanskaya, was the 1st Tank Army, which had two tank, one motorized and 6 infantry divisions. Kleist delivered the main blow east of the Salsk-Stalingrad railway with the task of reaching the Volga in the Krasnoarmeysk area. The Germans easily swept away the defenses of the 51st Army and moved to the northeast. At the same time, on the Romanovskaya - Remontnaya line, four infantry divisions of the 6th Romanian Corps were deployed to the southwest. Already on July 25, the 22nd Tank Division captured the Kotelnikovo station, and a day later reached the Aksai River at the Zhutovo station. There were no Soviet units on the southwestern front of the Stalingrad defensive perimeter.

To protect this direction, it was decided to advance the 13th Tank Corps and two rifle divisions with the headquarters of the 57th Army. The tank armies of Moskalenko and Kryuchenkin received orders to launch a powerful counterattack in the general direction of Verkhnebuzinovka, defeat the left wing of Paulus’s army and throw it back beyond the Chir.

However, on July 25, with the support of the entire 4th Air Fleet, the Germans launched a general offensive. The infantry of the 6th Army crossed the Don on both sides of Vertyachiy, the 4th Army Corps of General Shwedler established a crossing at Nizhnechirskaya. Within 24 hours, significant forces were transferred to the bridgeheads, and on July 27, tank corps rushed into the breakthrough. Disorganized counterattacks by the Soviet tank armies were repulsed with heavy losses. All these corps, brigades, divisions, formally united in the army, were scattered over a considerable area, had no communication with each other, and were not ready for coordinated combat operations. The newly-minted army commanders did not even have time to get to know the troops, let alone practice interaction and control. Tank driver mechanics had 3–5 hours of driving time, and the tanks themselves, assembled in haste and in violation of technology, broke down even before reaching the combat line. The equipment of the troops with anti-tank and anti-aircraft artillery can be called symbolic, there were no howitzers at all, there was a catastrophic shortage of rifle units, and “Stalin’s falcons” were completely invisible in the air. S.K. Moskalenko recalls with bitterness: “Enemy aviation operated in groups of two to three dozen aircraft, appearing above us every 20–25 minutes. Unfortunately, our 8th Air Army, apparently occupied in other directions, did not oppose anything to them.” Therefore, any movement of Soviet troops during the day was paralyzed “due to the strong impact of enemy aviation.”

By the evening of July 28, the leading battalions of the 3rd Tank Division crossed the interfluve and reached the Volga in the area of the villages of Rynok and Latoshinka north of Stalingrad. The railway lines approaching the city from the north and northwest were cut, and from that moment the river could no longer be used as a waterway. The German captain wrote in his diary: “We looked at the steppe stretching beyond the Volga. From here lay the route to Asia, and I was shocked.”

At the same time, the tank corps of the 4th Tank Army broke through the Soviet defenses in the center and, repelling counterattacks from Kalach, reached the middle city perimeter on the Chervlenaya River; Von Knobelsdorff's 24th Panzer Corps turned north, Geimer's 48th Panzer Corps aimed at Beketovka.

After a 150-km throw to Aksai, Kleist’s tanks stood for a day waiting for fuel, but already on July 28 they broke into the Abganerovo station, where they were again stopped by brigades of the 13th Tank Corps. On the right, the divisions of von Seydlitz's 51st Army Corps fanned out to the southeast.

During these days, Richthofen's aircraft repeatedly carried out massive raids on Stalingrad, piers and crossings. The city burned like a giant bonfire. Industrial enterprises and residential areas were destroyed. A hail of incendiary bombs fell on the wooden houses of the southwestern outskirts, everything here burned to the ground. The boxes of the high-rise buildings stood, but the ceilings collapsed. Oil storage facilities and oil tankers were on fire. Oil and kerosene flowed into the Volga in streams and burned on its surface.

The Stalingrad front burned and collapsed in exactly the same way.

On July 29, the 14th Panzer Division met in the Gumrak area with the 23rd Panzer Division advancing from the north, and the 48th Panzer Corps occupied Beketovka. On the southern front, Mackensen's tank divisions, covered by motorized infantry, struck at Plodovitoe and further to the north. By evening they broke into Krasnoarmeysk. From here, from the steep yar, rising 150 meters above the river level, the whole of Stalingrad, the bend of the Volga with the island of Sarpinsky and the Kalmyk steppes were clearly visible. General Gordov’s order to retreat from the “bag” to the inner line was given too late. The front headquarters was evacuated to the left bank of the Volga, in the area of the Yama farm, and to the west and south of Stalingrad two “cauldrons” were formed at once, in which the troops of four Soviet armies were methodically ground up. From the north, the Far Eastern divisions unsuccessfully tried to break through to them and restore contact with the city, attacking on the move, as they arrived, without artillery and air support - they were subordinated to the headquarters of the 21st Army. From a letter from Private Ya.A. Trushkova to his native Ussuri region: “I will describe our mediocre situation. We arrived at the front with great grief, upon arrival on the second day we entered into battle with German tanks and infantry, and we were smashed to smithereens, with little left of the division..."

In principle, Paulus has already completed his task. Stalingrad ceased to play the role of a major transport hub and weapons forge. The tractor-tank plant stopped, the Red October plant stopped producing armor steel, and the transportation of Baku oil along the Volga was stopped. German aviation bombarded the river with mines over a distance of 400 km from Kapmyshin to Nikolskoye. The final blockage of the waterway was to be done by batteries of 88-mm cannons deployed on the western bank. Given the urgent desire of the Russians to defend the ruins of Stalingrad remaining after the bombing, they could not have taken it. German radio already trumpeted to the whole world about the fall of “the famous city on the Volga, bearing the name of Stalin.” But the fact of the matter is that there was no one to defend him.

In the city, in addition to almost 400 thousand civilians, there remained the 10th Infantry Division of the NKVD, armed detachments of workers and police, and the most senior military commander was Colonel A.A. Saraev. The city was not prepared for defense in advance: there were no fortifications, barriers, or firing points, hastily laid barricades on the streets looked frivolous, ammunition and medicine were taken away. On July 30, a decisive assault followed from three directions, ending with the breakthrough of the “Greater Germany” division to the ferry crossing at Krasnaya Sloboda.

On August 1, Paulus was awarded the rank of Field Marshal. Dr. Goebbels launched into a speech about the world-historical significance of the victory on the Volga and the guiding star of National Socialism. Moscow recalled General Gordov, his further fate is unknown.

As an asymmetrical response, the Red Army tried, acting according to its own plan, to defeat Army Group Center or, at worst, the 9th German Army in the Rzhev-Sychevsky salient. However, a series of offensive operations carried out from July 5 to August 29 by troops of the Kalinin, Western, and Bryansk fronts ended with the loss of 300 thousand soldiers, including the death of the 39th Army. In the south, on July 30, two new fronts were formed: Don under the command of K.K. Rokossovsky and South-Eastern, which was headed by General A.I. Eremenko. The latter was supposed to organize defense along the eastern bank of the Volga and the line of lakes south of Stalingrad. Rokossovsky had the task of blocking the enemy’s path to the north.

“The wise commander, with whose name on the lips Soviet soldiers went into battle,” still believed that the German army, advancing on Stalingrad, was performing a “complex outflanking maneuver” with the aim of encircling Moscow. The Germans quickly equipped deep-echelon positions taking into account the upcoming winter, but they still “did not believe”:

“Comrade Stalin promptly figured out the plan of the German command, which was trying to create the impression that the main, and not secondary goal of the summer offensive of the German troops was the occupation of the oil-bearing regions of Grozny and Baku. In fact, the main goal was, as Comrade pointed out. Stalin, in order to bypass Moscow from the east, cut it off from the Volga and Ural rear and then strike at

Moscow and thereby end the war in 1942. By order of the Supreme Commander-in-Chief comrade. Stalin’s Soviet troops blocked the enemy’s path to the north, to the rear of Moscow.”

The Soviet General Staff was misled by the buildup of enemy forces in the Stalingrad area and its active actions to improve its positions. During August, the 8th Italian Army under General Gariboldi advanced to the Don. The Italians occupied the area from Pavlovskaya to the mouth of the Khoper River. Not relying too much on the combat effectiveness of the allies, the German command did not remove the divisions of the 29th Army Corps that occupied this line, but included them in the Italian and the 2nd Hungarian armies located upstream of the river. The Romanians were arriving, who were supposed to take the Volga bank under guard; General Strecker's 11th Corps was transferred from the OKH reserve to strengthen the 6th Army. In addition, at the beginning of August, Paulus conducted a private operation in the Northern direction with the aim of moving the front line away from Stalingrad. As a result, positions on the outer contour, passing along the Ilovaya and Berdiya rivers, were occupied, Dubovka and tens of thousands of cattle that had accumulated at Soviet crossings were captured. The German landing force landed on Sarpinsky Island, which made it possible to completely take control of movement along the Volga.

General Rokossovsky, as was customary in Soviet military science, led an active defense. From the reserve, the 24th, 66th, and 1st Guards Armies were transferred to the Don Front, which rushed into battle, one by one, and all together. However, the Red commanders did not yet know how to tear apart the correct defense. A special department of the front reported to the capital: “Leading staff at the headquarters do not believe in the reality of their own orders and believe that the troops, in their current condition, will not be able to break through the enemy’s defenses.” Managers, in turn, reported: “People are not trained and completely unprepared, many do not know how to use a rifle at all. Before going to war, a new division must be trained and prepared for at least a month. The command staff, both middle and senior, are tactically illiterate, cannot navigate the terrain and lose control of their units in battle.” To the above, it only remains to add that the Red Army soldiers of the Don Front were plump and dying of hunger. Fruitless attacks continued until mid-October.

In London and Washington, the situation of the Soviet Union was considered close to collapse. However, the sky over the British Empire was far from cloudless. Rommel's tanks were one throw away from Alexandria. The defeat of the Red Army created a threat to the Near and Middle East from the north. Already on July 5, the Middle Eastern Defense Committee reported to London:

“If the campaign in Russia turns out badly for the Russians, and you are unable to send us the required number of reinforcements in a timely manner, then we will be faced with a dilemma:

a) either our troops or as many of our bases and installations as possible will have to be transferred from Egypt to the northern flank in order to cover Iranian oil fields (and this would mean the loss of Egypt);

b) either we will need to continue our current policy and take the risk of losing Iranian oil fields.

We do not have the strength to defend both, and if we try to perform both of these tasks, we will not complete either...

In our worst case scenario, we should expect a threat to emerge in Northern Iran by October 15, and if the enemy changes its plans and moves through Anatolia Province, then we need to be prepared to meet this threat in Northern Syria and Iraq by September 10.”

The prime minister responded to this report with a letter in which he said that reinforcements could appear only after the defeat of Rommel in the Western Desert, and a serious threat to Iraq was unlikely to arise before the spring of 1943. On July 29, the Committee of Chiefs of Staff reaffirmed that the security of the Middle East was ensured in Cyrenaica. In the event of an unforeseen development of the situation, Abadan should be held until the last opportunity, “even at the risk of losing the Nile Delta region in Egypt.” The loss of Abadan could only be compensated for by an additional supply of 13.5 million tons of oil, which required finding 270 tankers. The report of the Committee on Control of Fuel Resources stated: “The loss of Abadan and Bahrain would lead to disastrous consequences, since it would cause a sharp reduction in all our capabilities to continue the war and, possibly, would force the abandonment of a number of areas.” Moreover, to protect Iran and Iraq there were only three infantry and one motorized divisions. The main forces of the British 9th Army had been stationed in Syria since July 1941, ready to repel enemy attacks through Turkey.

The Turkish government desperately maneuvered, trying to stay out of the global conflict and preserve the sovereignty and independence of the country. Ankara was concerned about both Rome's claims to dominance in the Mediterranean and Moscow's desire to control the Black Sea straits. In 1940, despite the existence of the British-French-Turkish alliance, Turkey declared itself a "non-belligerent state". The rapid defeat of Yugoslavia and Greece and the capture of the island of Crete by German troops in the spring of 1941 brought them to the borders of Turkey, creating a real threat of invasion. In Berlin, plans were thoughtfully worked out to advance to Iran and to the Suez Canal through the territory of Turkey, with which, by the way, a friendship treaty was signed, regardless of its consent: “If Turkey does not come over to our side even after the defeat of Soviet Russia, a blow to the south through Anatolia will be carried out against her will.” In the summer of 1942, the influence of the pro-German faction was steadily growing in the ruling circles of Turkey, calling for “not to miss the moment” and to take part in the division of Soviet Transcaucasia. The ideologists of “Great Turkey” became concerned about the fate of the “Azerbaijani Turks” and other Turkic peoples living east of the Volga. Beginning in mid-July, Turkish troops began to concentrate on the eastern border. The Chief of the General Staff, Marshal Cakmak, considered “Turkey’s entry into the war almost inevitable.”

As for the Arab countries, their population traditionally saw the British as colonialists, and in Hitler as a natural ally of the national liberation movement. In an effort to provide a strong rear, in formally independent Iraq, Iran, Syria, and Lebanon, the British were forced to establish occupation regimes with puppet governments. In Palestine and Transjordan, “irresponsible” Bedouins launched a real guerrilla war, posing a threat to the strategic Kirkuk-Haifa oil pipeline. In the north-west of Iran, a rebellion of Kurdish tribes flared up. Anti-British sentiment was fueled by German agents. For a direct invasion of the Middle East, the OKW headquarters decided to deploy the Special Purpose Corps "F".

The threat was also growing from the south. The Japanese capture of the Andaman Islands and Rangoon in March 1942 strengthened the position of their troops in Burma and created the threat of an invasion of India. In the first half of April, the 1st Air Fleet under the command of Vice Admiral Nagumo, with a swift raid of five aircraft carriers, disrupted shipping in the Bay of Bengal, destroyed the port facilities of Colombo and Trinco-mali, and sank all the British ships that came along the way, including the aircraft carrier Hermes and two heavy cruisers. The commander of the Eastern Fleet, Admiral Somerville, was forced to abandon the use of bases in Ceylon and the Maldives and withdraw his forces to the east coast of Africa in order to maintain control of at least the western part of the Indian Ocean, through which convoys to the Middle East passed. In early July, the Japanese launched an invasion of Ceylon. The naval battle off the island of Madagascar ended with the destruction of the Eastern Fleet, which consisted of two aircraft carriers and five battleships from the First World War as its main combat units. The capture of Ceylon allowed the Japanese to establish dominance in the Indian Ocean and disrupt British communications, not only with Australia and India, but also with the Middle East.

On August 12, Winston Churchill flew to Moscow to personally tell Comrade Stalin the most unpleasant news: a second front in Europe should not be expected in 1942. Military supplies are also not expected yet. On August 13, Stalin handed the British Prime Minister a memorandum in which he accused the British government of inflicting a “moral blow to the entire Soviet public” and destroying the plans of the Soviet command, built with the expectation of “creating in the West a serious base of resistance to the Nazi forces and facilitating such image of the situation of the Soviet troops." It was further argued that right now the most favorable situation had developed for the Allies to land on the continent, since the Red Army had diverted all the best forces of the Wehrmacht to itself. The Supreme Commander directly admitted that the Soviet Union was on the verge of defeat. Churchill threw up his hands and left for Cairo to organize the defense of British possessions. And the Soviet

The leader was finally convinced that the Anglo-American imperialists only wanted the weakening and destruction of “the world’s first proletarian state.”

Hitler had not yet received Caucasian oil, but had already deprived Stalin of it. All that remained was to “lay hands on the oil field area.”

On July 23, the Fuhrer signed Directive No. 45 to continue Operation Braunschweig. The main role this time was given to Army Group A, which included Hoth's 4th Panzer Army, Manstein's 11th Field Army, and the Italian Alpine Corps. Field Marshal List's immediate task was to encircle (by entering the motorized left wing) and destroy Soviet troops south and southeast of Rostov. In the future, they were to split into three groups. One was supposed to strike along the Black Sea coast, the other, reinforced with mountain units, on Armavir, Maykop and the Caucasian passes. The ultimate goal was to reach the regions of Tbilisi, Kutaisi, Sukhumi and take possession of the entire Eastern coast of the Black Sea. At the same time, another group, composed of tank and motorized formations, broke through to Grozny and Makhachkala in order to subsequently capture Baku with a blow along the Caspian Sea.